Kotlin vs Java in 2021

Since the arrival of Java 17, I've heard a few people wonder "Does Kotlin still make sense, or should I just use Java?"

My opinion: Kotlin is still a far better language, and some of its critical design features will never be matched in Java.

Null Safety and Immutability #

Kotlin lets you write elegant null-safe code, and forces you to be explicit about null-safety.

For example, consider this data class:

data class Person(val name: String)

Because of the val keyword, you can't forget to set name when instantiating a Person, and you can't set it to null later.

That's an entire class of nasty bugs wiped out with a single elegant language design.

Conversely, when something can be null, the compiler forces you to explicitly handle it in a concise manner, also giving you an escape hatch if you choose to be unsafe about it.

var b: String? = "abc"

b.length // compile error: variable 'b' can be null

// you must use a null-safe operator

b?.length // which evaluates to null if 'b' is null, or the length of 'b' if it is not null

// or you can add the `!!` operator to a call if you're willing to accept the possibility of a null pointer situation.

b!!.length

Java bolted on the Optional container to try to solve this problem, but it's clumsy and rarely used in the code I've

seen. That's a recurring theme in many of the features; Kotlin makes it easy to write concise and stable code.

This one's just really really important in my opinion, and is worth the price of admission on its own.

You could stop reading this article now and that's enough reason alone to use Kotlin in my opinion.

Official docs on null safety here.

Some of my favorite features #

Now for some reasons I really enjoy writing Kotlin. There are plenty of other features, but these are the favorites that come to mind.

Collection functions #

There's a ton of them, and they're powerful and pragmatic. Full docs here; some commonly used examples:

val numbersGreaterThanOne = listOf(1, 2).filter { it > 1 } // [2]

val stringLengths = listOf("bear", "cat").map { it.length } // [4, 3]

val firstTwoElements = listOf(2, 4, 6).take(2) // [2, 4]

val sum = listOf(1, 5).sumOf { it } // 6

Java has streams, but its a small fraction of what's available in Kotlin, and is again a bolt-on rather than integral part of the language. Java has dozens; Kotlin has hundreds.

Extension functions #

From the docs:

Kotlin provides the ability to extend a class with new functionality without having to inherit from the class or use design patterns such as Decorator. This is done via special declarations called extensions.

For example, add a utility function to Date that converts it to a UTC ZonedDateTime:

fun Date.toUtcZonedDateTime(): ZonedDateTime = ZonedDateTime.ofInstant(this.toInstant(), ZoneOffset.UTC)

val date = Date()

val zonedDateTime = date.toUtcZonedDateTime()

Another example, encapsulating a standard choice for a hashing algorithm so that usage is concise and easily refactorable:

import com.google.common.hash.Hashing

fun ByteArray.hash(): ByteArray = Hashing.murmur3_128().hashBytes(this).asBytes()

val hashedBytes = "abc".toByteArray().hash()

Once you start using them, you'll find all sorts of ways to make your code cleaner. You can create DSLs effortlessly, and add missing features to code while keeping it readable and easily testable.

Default and named arguments #

Default arguments are all about more compact, readable, and refactorable code. Named arguments give you readability when you want, and also reduce bugs in the case of multiple arguments with the same type.

fun makeHttpCall(url: String, timeoutSeconds: Int = 10, retries: Int = 3) { ... }

// all of these work

makeHttpCall(url = "http://foo.com", timeoutSeconds = 30, retries = 10)

makeHttpCall(url = "http://foo.com", timeoutSeconds = 30)

makeHttpCall(url = "http://foo.com", retries = 0)

makeHttpCall(url = "http://foo.com")

With Java, you still need gobs of overloads or builders, and even then without named arguments usage gets tricky.

public void makeHttpCall(String url) {

makeHttpCall(url, 30);

}

public void makeHttpCall(String url, int timeoutSeconds) {

makeHttpCall(url, timeoutSeconds, 3);

}

public void makeHttpCall(String url, int timeoutSeconds, int retries) {

// ...

}

makeHttpCall("http://foo.com", 30, 10);

// which arg is the timeout? hope i didn't screw up.

makeHttpCall("http://foo.com", 10);

makeHttpCall("http://foo.com");

// how do we call with just a url and retries?

// we'd need a new method that doesn't conflict with the

// existing method that takes a String and int.

Docs here

String interpolation #

val score = 1

println("the score is $score. The score minus one is ${score - 1}")

This is the cleanest string interpolation technique in my opinion.

Data classes and .copy() #

Java finally has records now. Something I use all the time though, especially when combined with

immutable data structures, is the copy function. For example a common test data setup

pattern looks something like this:

// in Person.kt

data class Person(val name: String, age: Int)

// in PersonTest.kt

fun randomPerson(): Person {

return Person(name = someRandomString, age = someRandomAge)

}

@Test fun testPerson() {

val bob = randomPerson().copy(name = "bob")

}

Function types as class parameters #

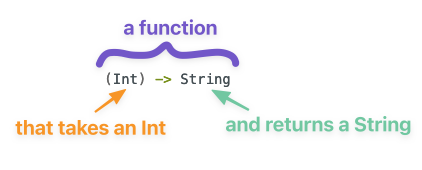

This is a really powerful and flexible capability. It does come at a slight cost in clarity, and IDE support is limited, but is preferred by myself and many others I've worked with. First off, what's a function type? Docs here, but the most common form I use looks like this:

(Int) -> String

which can be broken down like this:

An example function type that takes two Int parameters and returns a String would be:

(Int, Int) -> String

A function with no parameters that returns a String would be:

() -> String

A function that doesn't return a useful value must specify Unit. e.g.:

(Int) -> Unit

OK great - you can define functions that have a signature but don't have a name. What can we do with that? How about pure dependency injection without the need for mocks?

// a "real" DataRepository that saves data to a repository

class DataRepository {

fun saveStatus(status: String): Boolean {

// save the name to the database and return true if it was updated

}

}

// a "real" Publisher

class Publisher {

fun publishStatus(status: String) {

// publish the status via some integration

}

}

// a service that performs complex logic that needs to be unit tested

class FooService(

saveStatus: (String) -> Boolean,

publishStatus: (String) -> Unit

) {

fun handleStatus(status: String) {

saveStatus(status)

publishStatus(status)

}

}

// the class wiring up the real stuff together

class Application {

private val dataRepository = DataRepository()

private val publisher = Publisher()

private val fooService = FooService(

saveStatus = dataRepository::saveStatus,

publishStatus = publisher::publishStatus

)

// whatever else the application needs to do to get wired up and run

}

// the service unit tests

class FooServiceTest {

@Test fun `everything works great`() {

val fooService = FooService(

// set the saveStatus parameter to a lambda that ignores the String parameter and returns true

saveStatus = { _ -> true },

// set the publishStatus parameter to a lambda that ignores everything and returns Unit implicitly

publishStatus = { }

)

fooService.handleStatus("yay") // along with whatever assertions you want

}

@Test fun `saveStatus failure should do the right thing`() {

val fooService = FooService(

// set the saveStatus parameter to a lambda that blows up, simulating a problem in the repository

saveStatus = { _ -> throw RuntimeException("the sky is falling") },

// set the publishStatus parameter to a lambda that ignores everything and returns Unit implicitly

publishStatus = { }

)

// shouldThrow is an example feature of the fantastic kotest assertion library

// i.e. we've injected behavior into the service indicating a failure should happen

// and we should handle it properly

shouldThrow<RuntimeException> {

fooService.handleStatus("should fail")

}

}

}

No DI frameworks needed. No mocking needed. Just pure function signatures with full precise control of the contract

behaviors you're building and testing.

This works great for situations like this where you need to wire up a single production implementation and want one

or more test implementations. The compiler will keep the code honest. But, one caveat is that the Find Usages

functionality of the IDE doesn't work because the functions are too ambiguous for the current versions of IntelliJ.

That does add a little more mental overhead to maintenance, along with the mental overhead of the function type as a

parameter itself. But in practice this hasn't been an issue on my projects, and the benefits outweigh the drawbacks

in my opinion.

All that said, interfaces and regular old functions obviously still have their place and should be used where appropriate.

Lots more common idioms #

The Kotlin docs maintain a list of frequenty used idioms here. It's a great place for practical examples of good code.

- Previous: 50 Million Essential Homeowner Tools

- Next: Spring Rites